In summary – The FBI defines transnational repression as when foreign governments reach into the United States to intimidate members of their diaspora. California police say they want help identifying those incidents.

A seemingly noncontroversial proposal to help California police identify and address instances of violence motivated by international politics is hitting a nerve among South Asian communities who believe they could be targeted by the bill.

The new opposition to a law enforcement training bill by California’s only Sikh state lawmaker is reviving the battle lines from a bill Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed last year that would have banned caste discrimination in the state.

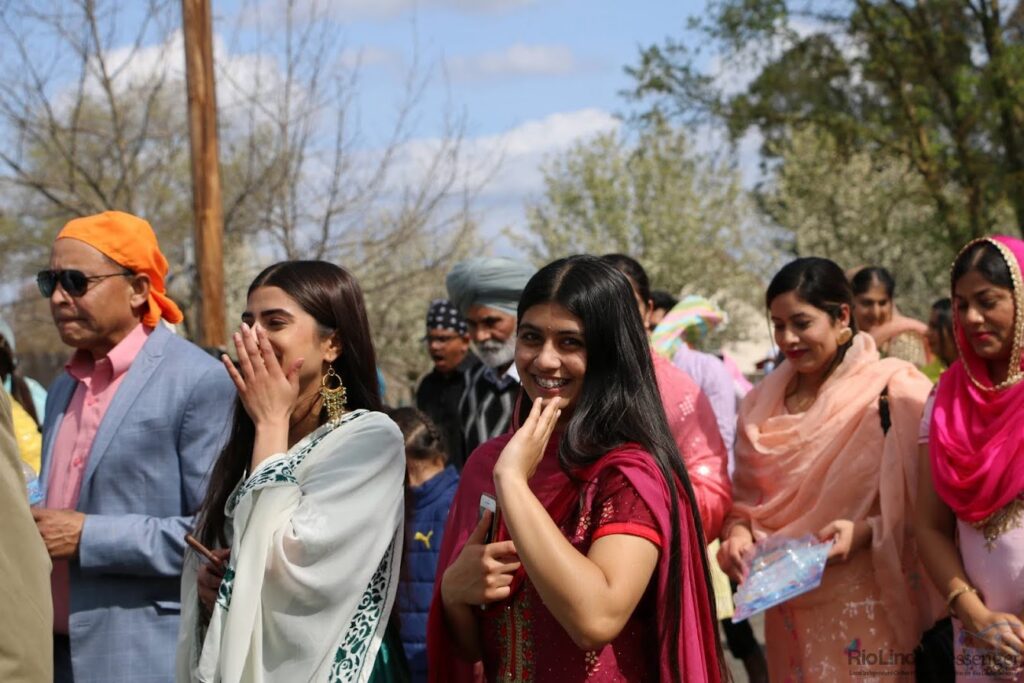

Assemblymember Jasmeet Bains wrote the new bill after the June 2023 killing of a prominent Sikh activist in Canada that set off a political rift between Canada and India. Hardeep Singh Nijjar’s slaying and a subsequent foiled plot in New York galvanized an estimated 127,000-plus Sikhs to cast a symbolic vote in San Francisco in favor of creating a separate Sikh state from India named Khalistan.

That movement and its tense history with India triggered backlash in the Golden State. Two Hindu temples in the Bay Area were defaced with anti-India and pro-Khalistan graffiti on the cusp of the new year, and the FBI has reportedly begun to visit and call some Sikhs in the state to warn their lives could be under threat.

Bains’ legislation, Assembly Bill 3027, would create a training program for law enforcement to combat and prevent transnational repression, which the FBI defines as foreign governments reaching into the United States to intimidate or harm members of their diaspora. The measure sailed through the Assembly unanimously in May and is coming up for a Senate Appropriations Committee hearing as soon as today.

“U.S. ally or not, India and other foreign governments violating our national sovereignty must be held accountable,” Bains, a Democrat from Bakersfield, said in May on the Assembly floor.

Much like last year’s caste legislation, though, the devil is in the details. The bill lists India alongside Russia, China and Iran as governments that “increasingly rely on transnational repression as their consolidation of control at home pushes dissidents abroad.”

Two of those states, Iran and Russia, have long been adversaries to the U.S., while the U.S. and China are economic rivals who often compete for geopolitical influence. India, by contrast, does not have as strong of a history of direct conflict with the United States. It is regarded as the world’s largest democracy, and has a thriving diaspora in the U.S.

South Asia experts and activists often challenge that view, pointing to the country’s Hindu nationalist government under Prime Minister Narendra Modi and division on the lines of caste, religion and class. Last year, those inequalities were on full display when California’s caste-diverse and often working class Sikh community largely backed last year’s anti-discrimination bill, while more-wealthy and caste-privileged Hindu Americans sought to derail it.

This year, some leading conservative Hindu activists oppose Bains’ law enforcement training bill. They want her to remove India from its language and believe the legislation risks teaching officers to overlook violence from the Sikh separatist movement.

They cite examples such as a report that separatists attempted to set fire to the Indian consulate in San Francisco the month after the Canada shooting, an accusation reported by India-aligned media but that the U.S. State Department has not publicly affirmed.

“If you are of Indian origin and if you are countering these radical groups — Islamists, Maoists or Khalistanis, this provision… can be used to silence you,” said Utsav Chakrabarti, executive director of the Hindu advocacy groups HinduPACT USA and HinduACTion during a livestream in July announcing opposition to the bill. “That’s a pretty dangerous situation to be in.”

Chakrabarti did not respond to requests for comment. The organizations have been linked to the Indian government. The Washington Post in a December investigation said both groups were a key spreader of an online campaign by Indian intelligence to discredit critics abroad. A member of HinduPACT told the Post at the time they were not aware of the campaign’s origins and denied any wrongdoing.

Transnational repression in California

Law enforcement agencies, including the California State Sheriff’s Association, support Bains’ bill. They’re looking for training and guidance on crimes that appear motivated by international events.

California, home to more immigrants than any other state, is particularly susceptible.

One prominent California case goes back to 2020, when a Russian asylum seeker was detained in an ICE facility after the Russian government used international alerts to U.S. authorities to accuse him of criminal activity.

He endorsed Bains’ bill.

“My story underscores the pressing need for legislative action to safeguard California residents from international oppression,” wrote Gregory Duralev, now an Orange County resident, in an April statement.

In Kern County, on the southern end of the Central Valley home to over 30,000 Sikhs and several Sikh temples, a lack of training among officers has made it difficult to track the prevalence of transnational repression, Sheriff Donny Youngblood told CalMatters.

Currently, officers would probably log such concerns “as a threat” but “in fact, it could go much deeper than that,” he said, such as retribution toward a person’s family by a government back home. “This is a huge issue that really is relatively new to law enforcement.”

The Legislature is well aware of the plight of Sikhs in India. Last July, lawmakers swiftly approved Bains’ resolution that recognized anti-Sikh mobs in 1984 India as a genocide.

Many Sikhs in California who fled that violence “are very concerned about the safety and risk of their loved ones, their children, their folks who are engaged in local politics or who do vocalize their political opinions about India,” said Puneet Kaur, senior state policy manager for the Sikh Coalition, a national civil rights advocacy group. “A huge part of the reason that communities, including Sikhs, migrated here (was) for the purpose of freedom and escaping violence.”

The Indian government has denied allegations by the Canadian government regarding the killing of Nijjar. Indian authorities have previously accused him of terrorism. Bains’ legislation says the training should teach officers that accusations like that can be used by repressive governments to target dissidents abroad, and it’s not just for immigrants from India.

Around the world, 854 direct incidents of transnational repression occurred between 2014 and 2022, according to a 2023 report from Freedom House, a nonprofit organization that tracks such cases.

What will Newsom do?

It’s not yet clear whether Newsom is ready to send a strong rebuke to the governments called out in Bains’ bill. Newsom visited China in October to promote a climate partnership with California.

He also visited India in 2009 when he was mayor of San Francisco.

Recently, South Asian news outlets reported that the governor met with a prominent opponent to last year’s caste legislation.

In early July, Newsom met with Ramesh Kapur, an Indian American political donor who told the San Francisco Chronicle in October 2023 that he helped persuade Newsom to veto the caste bill. Kapur later walked back that statement to the Chronicle and other media, telling the Post that he let the governor know he couldn’t take his support for granted.

Kapur donated $27,000 for the governor’s Campaign for Democracy initiative from April to May, campaign finance records show. He also held a Bay Area fundraiser for Newsom in June, according to the publication Indica News.

Newsom’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

His office previously told CalMatters that the governor met with individuals on all sides of the issue, denying that any one meeting influenced his decision. The governor wrote in his veto message last October that the caste bill was legally “unnecessary.”

At Kapur’s Massachusetts home on July 7, Kapur reportedly thanked the governor for last year’s veto and the two affirmed the role of Indian Americans in the state, according to New India Abroad.

Kapur’s pro-India advocacy organization did not respond to requests for comment.

Last year, the caste bill’s author, Sen. Aisha Wahab, a Democrat from Hayward, faced death threats and xenophobic attacks upon introducing the legislation. Bains, one of California’s two South Asian lawmakers and a co-sponsor of that legislation, did not speak out publicly about her support.

This time, she has yet to receive any public opposition from lawmakers.

“In California, where we embrace our diaspora and exile communities, Republicans and Democrats have unanimously supported my legislation,” she wrote in a statement to CalMatters. “My bill simply makes it the policy of the state to protect Americans from foreign governments and gives law enforcement the training and tools to recognize the signs of transnational repression.”

Different views on transnational repression bill

Not all Hindus in California oppose Bains’ bill, and some say they have seen the effects of India’s politics on their ability to express themselves. The liberal group Hindus for Human Rights is blocked on X, formerly known as Twitter, in India.

Raju Rajagopal, a Berkeley-based Hindu activist and a key founder of that group, has long battled with Hindu groups on the right. Bains’ legislation hasn’t sparked the crowds that held rallies over last year’s caste bill, but he said he is hopeful that will happen if opposition from the right grows.

As wounds from last year linger, though, some who oppose Bains’ effort are less confident about their ability to stop the bill.

Jeevan Zutshi, a real estate broker and activist known in many Hindu American circles, said he believes those who accuse other Indians Americans of domestic terrorism could be labeled as foreign agents if the bill is passed. But he noted that last year’s caste bill sailed through the Legislature even though Hindu groups fiercely pushed back.

He’s well aware of the concern about the graffiti on Bay Area Hindu temples. At the same time, he cautioned, authorities there have yet to make an arrest or publicly identify a suspect. Local and national Sikh groups condemned the vandalism at the time.

“We have to be very careful in our life before you start some kind of accusation without evidence, or you make comments which are not healthy for relationships and bringing people together,” he said from his Fremont home. “Sometimes hate begets hate.”

Written by Shaanth Nanguneri of CalMatters, a Rio Linda Online contributor.