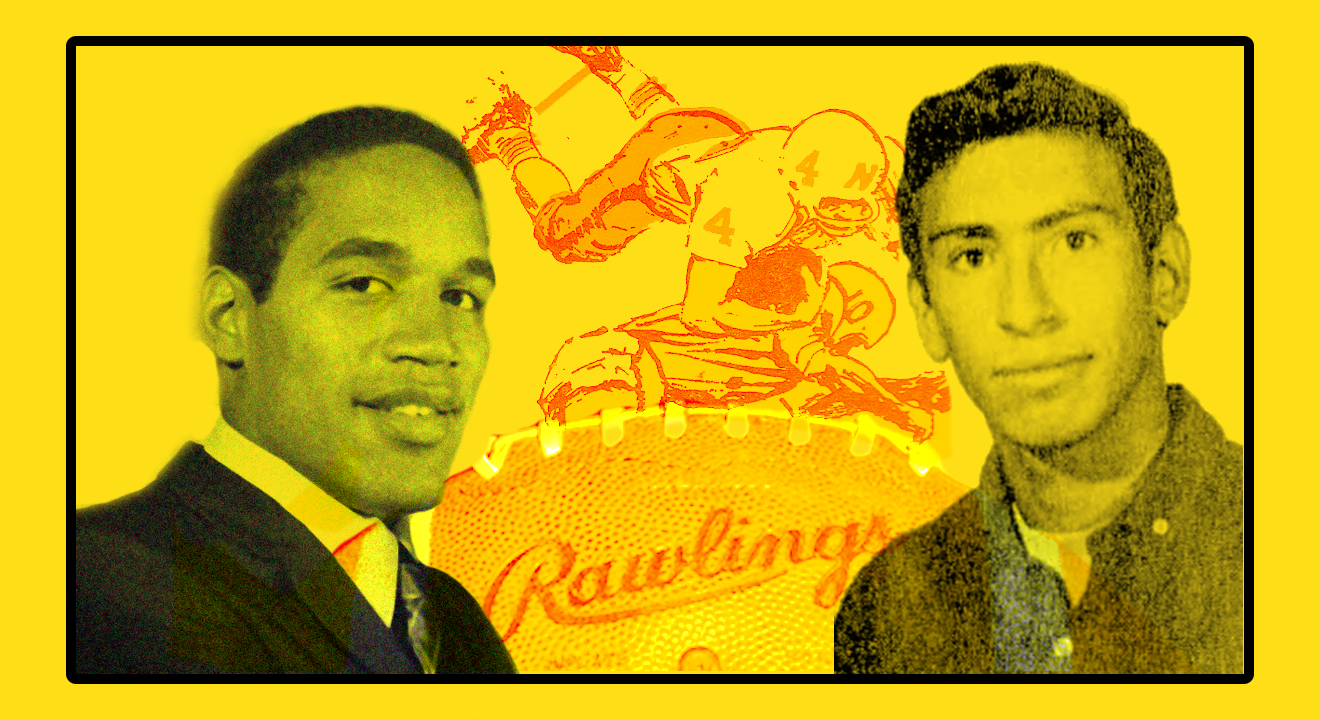

With the recent death of OJ Simpson, it should be noted for those who don’t know, how OJ and Rio Linda were tragically linked through football, and how Simpson could have done more for a Rio Linda family, and more for the NFL, it’s players, and the game of football.

On November 10th, 1967, Rio Linda High School was hosting the Elk Grove Herd in a late-season football game. It was being played at Highlands High School since Rio Linda did not yet have a stadium of its own.

5-foot-6, 135-pound Junior Ernie Pelton received the 2nd half kickoff for the Knights and was violently tackled by two Elk Grove players.

It’s said that the hit was so loud and brutal that it made players and fans both recoil in shock, and it was loud enough to quiet the entire stadium. The impact of the tackle dropped Pelton to the ground, cracking his chinstrap in half and snapping his neck back forcefully.

As he stumbled back to the bench, nobody suspected that those would be the last steps he would ever take.

In March 1970, the family of Ernie Pelton sued Rawlings Sporting Goods, the maker of the helmet that Ernie was wearing that day, for $3.6 million. OJ Simpson, a Heisman Trophy winner and first-round draft pick, defended the helmet manufacturer, stating his trust in the helmets he used during his career with the Buffalo Bills.

At the trial, held in Sacramento County Superior Court, Simpson, wearing a Rawlings helmet throughout his career, confidently stated, “I believe in this helmet. I know every time I get on the field, there’s a chance I get hurt.”

His charm and fame likely influenced the jury, which later requested photos with him, as reported by the Sacramento Bee.

Despite the warning inside the helmet advising players to “avoid all purposeful contact,” Simpson admitted he found this challenging.

His testimony resonated with the jury, which ultimately ruled in favor of Rawlings.

After a five-month trial, it took a jury of seven women and five men less than three hours to decide in favor of Rawlings and the Grant Union High School District (which later became the Twin Rivers Unified School District).

The Pelton family was awarded nothing.

This verdict set a precedent that helped shield the NFL from liability concerning the dangers of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) for many years. The ruling discouraged legal challenges against helmet manufacturers for decades, despite a few cases like the 1974 Rhode Island ruling against MacGregor and a 1975 victory against Rawlings by the family of a young Indiana player.

As the NFL grew in popularity, the focus on player safety lagged. It wasn’t until the tragic suicides of former players like Dave Duerson and Junior Seau, who were diagnosed with CTE post-mortem, that the NFL began to address the issue more seriously. The league has since improved helmet safety through rigorous testing, but critics argue that these measures are insufficient given the increase in concussions and the extended season length.

Simpson himself expressed concerns about having CTE in 2018, acknowledging the effects of concussions he suffered during his career. Yet, his decision to keep his medical records private continues to spark debate, with many feeling that an opportunity for greater awareness and understanding of CTE was missed with his passing.

The NFL’s stance on helmet safety shifted significantly only after it could no longer ignore the mounting evidence of brain injuries among its players. This change came too late for Pelton, who spent his life severely disabled, with his family attributing their legal loss partly to Simpson’s influential testimony.

Ernie Pelton spent the rest of his life as a quadriplegic, with a shunt inside his skull which relieved pressure on his brain. The hit he suffered separated the nerve endings between his spinal cord and brain, leaving him paralyzed from the neck down. He had limited movement in his right hand and could speak, with difficulty.

He spent the last 35 years in a pink and white house in south Sacramento, his small bedroom filled with medical equipment and wires plugged into every available power outlet.

He occupied his days by watching TV.

In 2007, Ernie battled pneumonia for weeks, but finally succumbed on September 9th. He was 57 years old. Ernie was buried on September 18th at Sunset Lawn Chapel of the Chimes, where so many of our Rio Linda and Elverta family members rest.

His Number 40 jersey which had been kept for 40 years by his brother Bob served as a drape over Ernie’s casket.

As the saying goes, “Once a Knight, Always a Knight.”

In October of 2008, 41 years later, Rio Linda High School retired Ernie Pelton’s jersey. No football player will ever wear the number 40 again.

(To find out more about Ernie Pelton and the Rawlings helmet trial, read the two-part series penned by Melody Gutierrez in the Sacramento Bee, November 28-29, 2007, and October 11, 2008.)